36 |

Oilfield Technology

May/June 2020

The wellhead, casing, and valves were then examined for

damage. With no apparent structural damage, Wild Well then

delivered the well back to the operating company to continue the

removal of tubing and installation of the new production system.

Whatwentwrong?

Often, when root cause analysis of an out of control well is

performed, humans focus on functional causes: faulty equipment,

improper procedure or human factors. Perception bias, in the

absence of critical thinking, plays a key role in out of control events,

as demonstrated in the case study. In this example, an initial review

determined that the crew did everything correctly, or at least the way

things have always been done in that field. Hundreds of similar wells

had been killed in the same manner without an incident. So what

went wrong with this well?

The operating company and the crew perceived an older pressure

depleted well. Confirmation bias encouraged the belief that a simple

reverse circulation would do the job because this had worked many

times before. The perception was that the reverse circulation could

be accomplished with an inoperable casing gauge by simply using

the pump gauge – another example of confirmation bias. They

perceived they did not need an operable gauge. A third instance of

confirmation bias based upon perception was that all hydrocarbons

had been removed from the well, since kill fluid had returned to the

surface, although the barrels pumped were 13 shy of the calculated

133 needed.

Howtomitigateor removethehazard

Older wells can accumulate methane gas, collecting it in various

‘traps.’ Confirmation bias created a situation where humans took

shortcuts to improve work efficiency because this had always

worked before. Reverse circulation is normally faster than forward

circulation. To save time, the engineers and management directed

the crew to perform the reverse circulation, with neither of the three

groups realising the risks involved. A forward circulation would have

removed the hazard.

The second example of confirmation bias was that the job

could be done efficiently without taking time to fix a piece of

faulty equipment. The inoperable casing gauge should have been

replaced with a working gauge. The data gathered from the working

gauge would have allowed the crew to properly analyse what

was happening.

If the gauge had been replaced, the crew would have seen that

even though the post-kill SITP recorded zero pressure, the SICP

would have shown pressure above zero. This data would have

shown that there was a difference in hydrostatic pressure between

the annulus and the tubing. If kill fluid had truly been circulated

completely throughout the well, the same fluid would be inside the

tubing as outside the tubing and the gauges would have read the

same number. Differences between the two gauges indicate either

another circulation has to be performed to remove all hydrocarbons

or the type of circulation has to be changed to properly kill the well.

The crew perceived that all hydrocarbons had been removed

from the well, since kill fluid returned to the surface via the tubing.

The difference between the 133 calculated bbl vs the 120 actual bbl

pumped is crucial information in this example. If calculations were

accurate and kill fluid returned to surface at 120 bbl, something had

to be taking up the 13 bbl of additional annular space: either oil or

gas. Though there are other reasons kill fluid could return early, in

this case it was gas which migrated to the surface as the BPV was

being installed. Working from perception without thinking about

why a phenomenon is being observed can result in disaster. Teaching

crews to think about an operation instead of simply doing the job

greatly reduces the possibility of out of control wells.

Theremedy

In this case study, taking the time to think about the well, repair

faulty equipment and understand how to read gauges in relation to

well control would have prevented the event. With this operation, the

solution would have been for the crew to forward circulate the well

to be certain that all the gas was removed from the annulus before

removing the production tree.

If perception is the way humans see and interpret phenomenon

in their environment and essentially how they live their lives,

upstream petroleum workers need to be aware of the risks of relying

simply upon perception and its biases to make decisions. Perception

without critical thought can often get workers into trouble.

Thus, workers need to first be properly trained in well control

that is specific to their operations. Second, crews should be taught

about and learn how to avoid the confirmation bias of doing what has

always been previously done. Third, both office personnel and field

crews need to learn to critically think about the specifics of a current

operation. Simply put, everyone needs to be trained and encouraged

to stop and think.

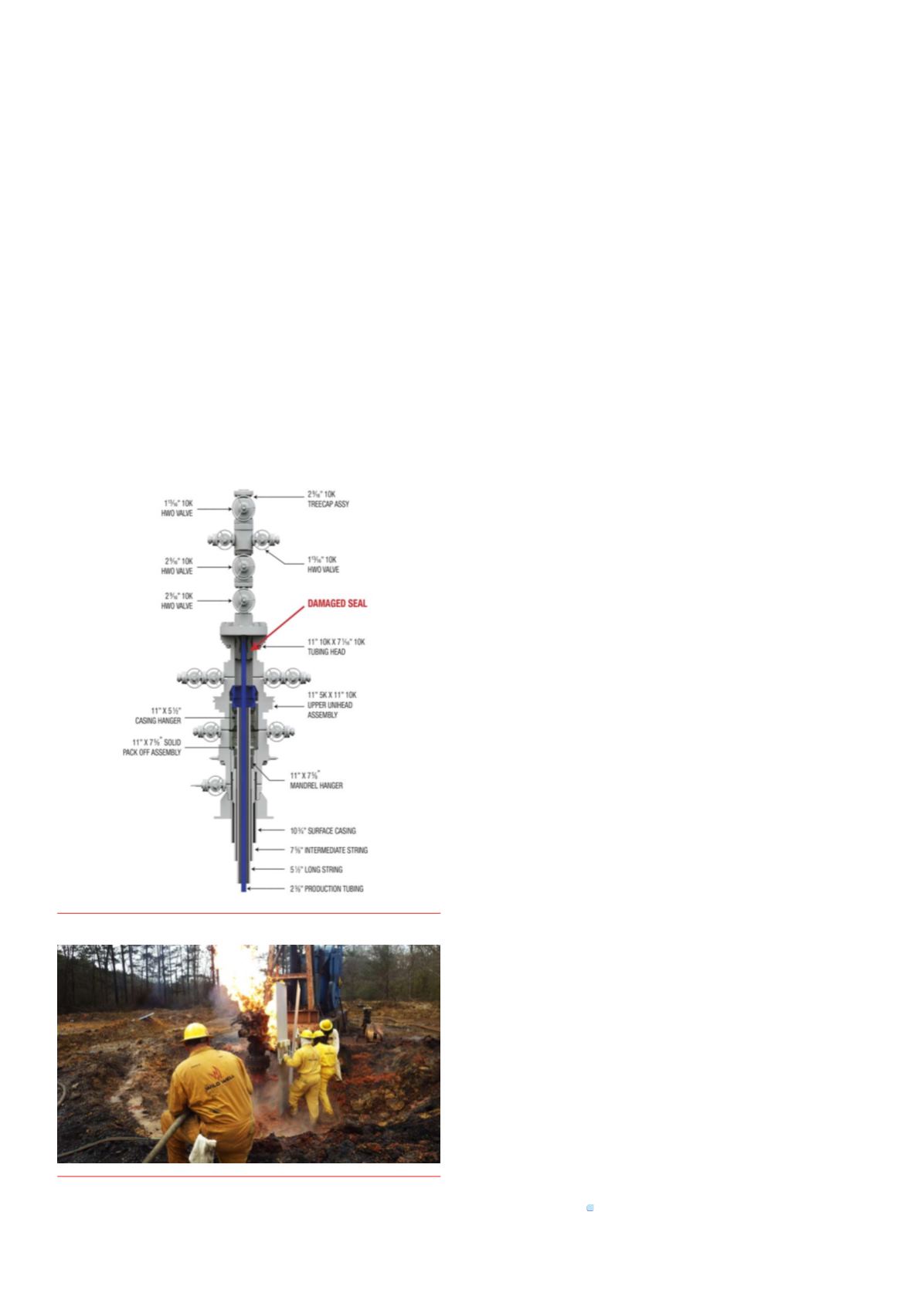

Figure 2.

Well control specialists inspect blowout well to prepare for well

kill operations.

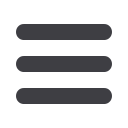

Figure 1.

Production treewith amechanical failure.