12 |

Oilfield Technology

May/June 2020

For many Asian countries, which are major consumers and

importers of crude oil, the COVID-crash might appear to be a

once-in-a-lifetime buying opportunity to fill their strategic reserves

and stock up before prices resume an uptrend. However, as any

commodity trader will know, picking the low point in the market is

never easy and over-committing to deliveries for which there is no

storage or refining capacity is a high-risk game. Who would ever have

expected that crude oil production and ownership could become a

waste disposal problem?

What is theroot causeof theCOVID-crash?

Debates may rage for years about whether the market pricing

structure was simply not set up for this ‘black swan’ event or whether

geopolitical tensions also played a role in the COVID-crash. Could

oil producers have cut crude production deeper and faster? Should

they have reacted sooner to early warning indications from Chinese

economic data that additional international coronavirus lockdowns

would cause a more significant demand slump on a global scale?

Incredulity, curiosity, a desire to analyse, the need to understand and

a willingness to learn will all lead to the question: ‘Why did the oil

price crash so dramatically?’

The simple answer is that supply and demand very quickly

fell out of balance. There was an abrupt reduction in aviation,

maritime, rail and road travel – causing a waterfall decline in refined

products demand. Chemicals and plastics plants cut back their

processing volumes, as a result of falling demand, as production

lines in industries such as automotives and textiles shut down –

pulling through fewer oil-derived petrochemical products. Electricity

production slumped in line with the drop in industrial activity; fuel oil

demand for power generation dropped accordingly. However, in Asia,

the Pacific, the Americas, Africa, Europe and the Middle East, indeed

all around the world, millions of barrels of crude more than the world

could consume kept on being produced per day.

Will land-lockedproducersbehithardestbythe

COVID-crash?

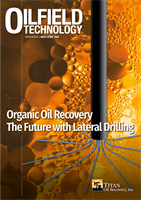

In any supply chain, storage between two processing steps is the

buffer that absorbs short-term swings in demand. Static storage

in the crude supply chain is fixed. However, redundant oil tankers

can be used as temporary additional storage capacity. For offshore

upstream operations, such as Malaysian rigs in the South China Sea

or Australian production in the Bonaparte and Carnarvon Basins

in the Indian Ocean, the use of tankers to store excess crude is

conceivable.

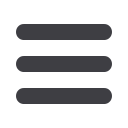

This is not the case for Asia’s land-locked producers. Shuttering

wells is expensive, but for onshore producers that outcome may

come sooner than for offshore and nearshore producers. On the

other hand, production cuts in other regions may redress the supply

and demand balance and trigger an upward move in local demand

and pricing just in time to save the day. Waiting for this to happen is

a high-risk strategy based on hope however, and hope is not always

the best decision-making tool. With this in mind, it is expected that

land-locked producers with limited access to storage will be the first

in line to shutter up their wells. Asia seems to be weathering the

storm at present, but at the time of writing the US rig count has fallen

40% from 650 to 380.

Oil storageconstruction investmentahead?

Pricing volatility can be a reason to minimise inventory to reduce

the risk of getting caught on the wrong side of a fall in price. On the

other hand, security of supply and the temptation to ‘buy the dip’

are reasons to invest in inventory and increase storage capacity.

Figure 1.

SouthChina Seadrilling rigand support vessels.

Figure 2.

Tazhong oilfield in Xinjiang, China.

Figure 3.

Oilfield support vessel in Labuan, Malaysia.

Figure 4.

Oil tanker in Singapore harbour.